Please note: the following was written by Openlands President and CEO, Jerry Adelmann, who coordinated Openlands’ efforts to establish the nation’s first National Heritage Area along the route of the historic Illinois and Michigan Canal.

Throughout the 20th Century, the Chicago metropolitan region repeatedly distinguished itself as an innovator in the fields of urban planning and open space preservation. The 1909 Plan of Chicago and the subsequent creation of the Forest Preserves of Cook County are both acknowledged as global models of open space planning.

One of these trail-blazing efforts, which Openlands led, was the creation of the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor in 1984—America’s first Congressionally-designated National Heritage Area (NHA) and the prototype for 48 additional heritage areas that have followed. NHAs tell stories about America’s past, while offering a place to enjoy nature through sightseeing and recreation. However,this innovative and wildly popular program is at risk.

In both 2017 and 2018, the White House attempted to eliminate all Federal support for the National Heritage Areas. Congress offers less than $1 million to local partners who maintain NHAs and ensure they are publicly accessible. Each federal $1 is leveraged by $4-6 in local funds. Luckily, due to sustained advocacy campaigns from organizations like Openlands, those funding cuts were beaten back both times.

NHAs are important to Illinois and one in particular, the I&M Canal Corridor, is important to me.

Photo: Canal Corridor Association (Canal Tourism Boat at LaSalle-Peru)

The Illinois and Michigan Canal: The Waterway that Made Chicago

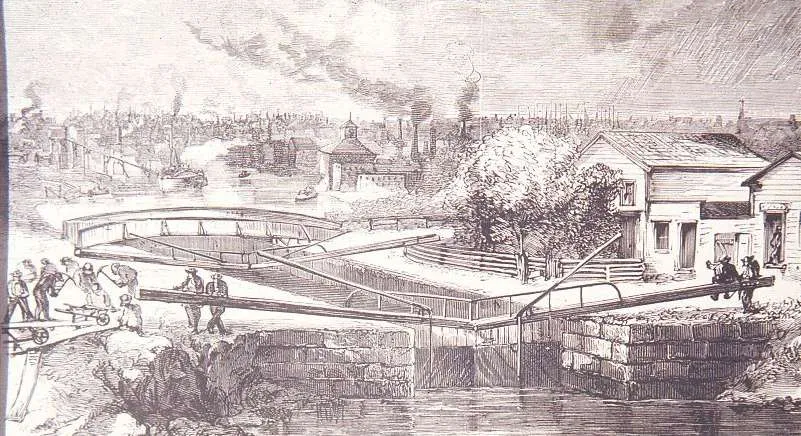

One cannot overestimate the seminal role the Illinois and Michigan Canal (I&M Canal) played in the founding and early history of Chicago. This pioneering waterway connected Lake Michigan at Chicago with the Illinois River 100 miles to the southwest at LaSalle-Peru. First envisioned by the French explorers Pere Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673, the hand-dug waterway provided a critical connecting link between the Atlantic seaboard, the Great Lakes, and the Gulf of Mexico. When the I&M Canal was completed it 1848, it positioned Chicago as a gateway to the West, and as America’s most important inland port and transportation hub.

Newer waterways were established paralleling the I&M, and this historic canal was finally closed for commercial use in 1933. During the years preceding World War II, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) transformed the canal into a park of great natural beauty and unparalleled recreational opportunities in northeastern Illinois. Miles of towpath were converted into hiking and bicycling trails; sections of the canal, its locks, and other related structures were rehabilitated; picnic areas and shelters were constructed along the canal’s banks; and state and local parks were developed on adjacent lands.

After the CCC was dissolved, however, most of the extensive improvements accomplished by this highly successful and popular project fell into disrepair. In the late 1950s, the easternmost section of the canal was used for the construction of the Stevenson Expressway (I-55) and the State of Illinois was preparing to sell off the extension real estate holdings along the canal’s route for private development. As local interest groups along the canal looked to preserve their region’s cultural and ecological legacy, they turned to a newly-formed not-for-profit called Openlands

Operation Green-Strip

Openlands, one of the first conservation organizations in the U.S. to work in a metropolitan area, organized local leaders and grassroots advocates to launch a preservation campaign called “Operation Green-Strip.” These efforts culminated in 1974 with the establishment of the 60-mile Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail.

Sections of the canal north of Joliet were excluded as they were fragmented with development that precluded a traditional linear park, yet many of these northern communities were some of the greatest supporters for preservation. Advocates kept coming back to Openlands asking for assistance to protect sections of the canal, important remnant natural areas, archeological sites, and other significant open space and cultural assets along the lower DesPlaines River Valley.

It is in the late 1970s when I entered the scene. A sixth-generation resident of Lockport, I realized that the future of the former canal headquarters was very much tied to a broader regional strategy along the route of the I&M. Collectively the resources of the historic canal towns and adjacent landscapes represented a rich chapter in the history of Illinois and the nation and, if coordinated, could serve as a catalyst to help revitalize this classic rustbelt corridor that was experiencing some of the greatest unemployment in the nation.

Working on a pre-doctoral fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, I became involved in volunteer projects to save some of Lockport’s historic buildings and unique natural areas, including the ecologically-rare Lockport Prairie. The Forest Preserve District of Will County suggested I contact Openlands with my ideas for a regional landscape-scale approach that would include recreational trails, revitalized waterfronts and historic downtowns, and protected natural and cultural treasures throughout the five-county region.

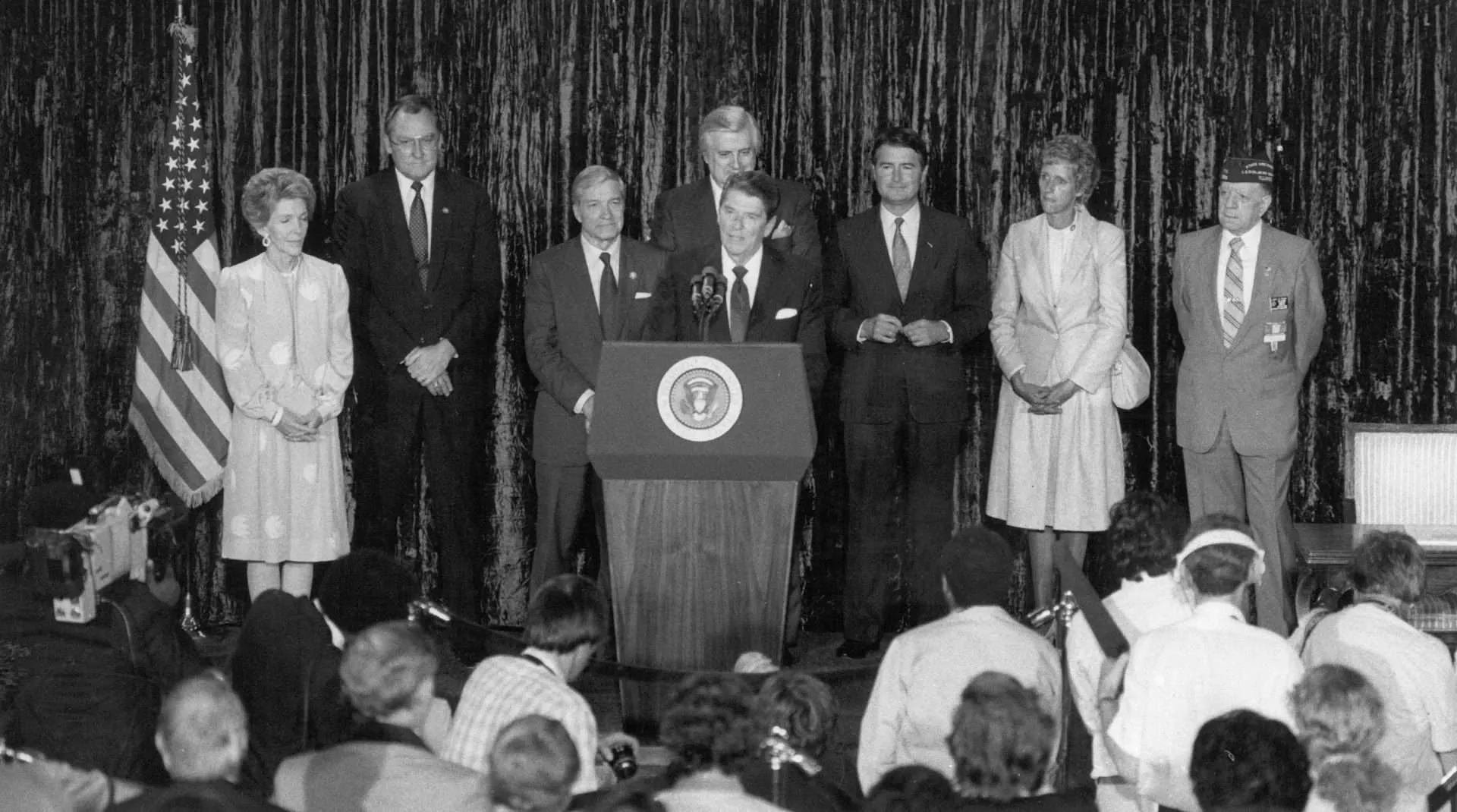

Openlands embraced the concept and provided critical leadership to move this concept towards reality. The Canal Corridor Association was established in 1982 as an independent not-for-profit, and in 1984 President Reagan came to Chicago to sign legislation that created the nation’s first heritage area, launching a national movement.

Enshrining our national heritage

National Heritage Areas combine ecological, cultural, and economic goals, and take a holistic approach to living, working landscapes. The overarching goal is to improve the quality of life for residents and visitors alike. They are “partnership parks” that leverage public and private resources, as well as civic leadership.

The role of the Federal Government is quite limited, but nevertheless crucial: federal designation elevates the significance of these areas as well as the social and cultural histories they represent. Modest funding and technical assistance over the years has supported region-wide coordination with wayfinding and interpretation. Hundreds of millions of private and public dollars have been reinvested in the I&M Canal region since its designation. Tourism and community economic development projects have added countless new jobs to these historic communities.

Positive outcomes like this are seen in the other heritage areas across the nation where modest federal support leverages reinvestment while addressing much need recreational needs and underrepresented stories in the American experience.

The I&M Canal National Heritage Corridor and future NHAs, such as two proposed NHAs in the Chicago region, the Calumet National Heritage Area and the Black Metropolis National Heritage Area, deserve full support from the Federal government.

Since its founding in 1963, Openlands has played a leadership role in most of our region’s innovative open space initiatives, including the creation of the nation’s first rail-to-trail conversion (the Illinois Prairie Path), the nation’s first national tallgrass prairie, and the first national wildlife refuge in the greater Milwaukee-Chicago area.

We will continue to support these projects, ensure their value is understood at every level, and most of all, defend the public’s right to access and enjoy them.

Updated: Congress has passed a budget that increases support for the National Heritage Areas. Learn more…